A headless bard, strumming on a three-stringed instrument called the sanxian, sits leisurely on an exposed root of a great gnarled tree, seemingly alone within a brown, parched wilderness of grass and bushes. Yet from the skies, several cloaked figures give chase to a fleet-footed Sun Wukong, the eponymous hero of Black Myth: Wukong, as he carves a bloody path towards a derelict temple. It’s a breathtaking introduction to the latest trailer for the soulslike game, developed by Chinese indie studio Game Science, with a release date that’s slated for 2024.

The global buzz around Black Myth: Wukong may be gradually reaching fever pitch, but the excitement over the game feels like it has peaked back in China, with local publications referring to Black Myth: Wukong as the pinnacle of locally-made AAA games. When it was introduced in 2020 with a 13-minute pre-alpha trailer, Black Myth: Wukong was met with international acclaim for its sleek, cinematic visuals and high-octane, high-fantasy combat scenes. Within a day of its release, the video had garnered 2 million views on Youtube and 10 million views on Chinese streaming site Bilibili. At the height of this commotion around Black Myth: Wukong, Game Science even had to fend off unsolicited visitors at its studio by putting up a notice outside its premises, according to a report from IGN China. One intruder, who thought the office would be vacant on a Saturday afternoon, broke into the building through a window to pay the studio a visit—a stunt that shocked the employees who were working at the office over the weekend. In another incident, a visitor abruptly turned up at the door, declaring that they had quit their job to participate in the game’s development.

For an indie studio that has only released mobile titles within the country, this widespread acclaim over Black Myth: Wukong is a largely unprecedented feat, particularly for a game that has not been released yet. But beneath the luster of this souls-like is a studio plagued by claims of sexism. Several posts have surfaced from Chinese social media site Weibo, written by individuals from the studio, that contain multiple references to genitalia and sexual innuendos. These have provoked a backlash among some in the games community, many of whom are women. This was coupled by recruitment posters by the studio, produced in 2015, which featured images and headlines that point to a culture of ingrained sexism in Game Science.

IGN spoke to several women familiar with gaming culture, as well as the games and technology industry, in China, many of whom requested to be anonymous for fear of backlash from fans of Game Science and the broader games community. “In the eyes of many female players, [Game Science] has a notably negative reputation,” said Jen (pseudonym), a Chinese games designer who’s now based outside of China. “I admire their dedication and work. I had high expectations for their game, until I came across their misogynistic remarks around 2021, which was reported in the news.”

IGN reached out to Game Science ahead of the publication of this article, but the studio did not respond to a request for comment on any of the allegations.

[CW: This article contains a number of quotes from Game Science that contain graphic sexual content and remarks.]

Founded in 2014, Game Science is a Hangzhou-based studio formed initially by seven ex-Tencent Games employees. During their time in Tencent Games, they worked on a free-to-play MMORPG called Asura Online. Black Myth: Wukong can be said to be the spiritual successor of this MMO, with both games based on the Chinese literary classic “Journey to the West”. Asura Online also featured mythological figures from the novel, such as Sun Wukong, the Bull Demon King, and Erlang Shen alongside a dark retelling of the novel, filled with several cinematic sequences. But to many of its fans, these were derailed by Tencent’s push for microtransactions in the game—a change that, according to one player, swiftly knocked Asura Online off the altar and turned it into a “trash game”. A year later, Feng Ji, one of the co-founders of Game Science, left to form Game Science along with his colleagues. After releasing a slew of mobile games, Game Science decided to focus on the development of Black Myth: Wukong in 2017.

Feng, in particular, has an outsized presence within the games industry, with a penchant for sharing introspective insights on game development, peppered with crude metaphors and boorish innuendos. In 2007, he penned a lengthy article titled, “Who has murdered our game?”, where he delved into the difficulties of game development in China. Feng compared failed projects to stillborn babies, given that many games had to cease development despite being worked on for a year or so. He then brought up this analogy:

“Is it because the sperm isn’t virile enough? Is the pregnancy too short? Is the baby lacking nutrition? Are the doctors in charge of caesarean sections lowly skilled? Why can’t we produce a healthy child (product)?”

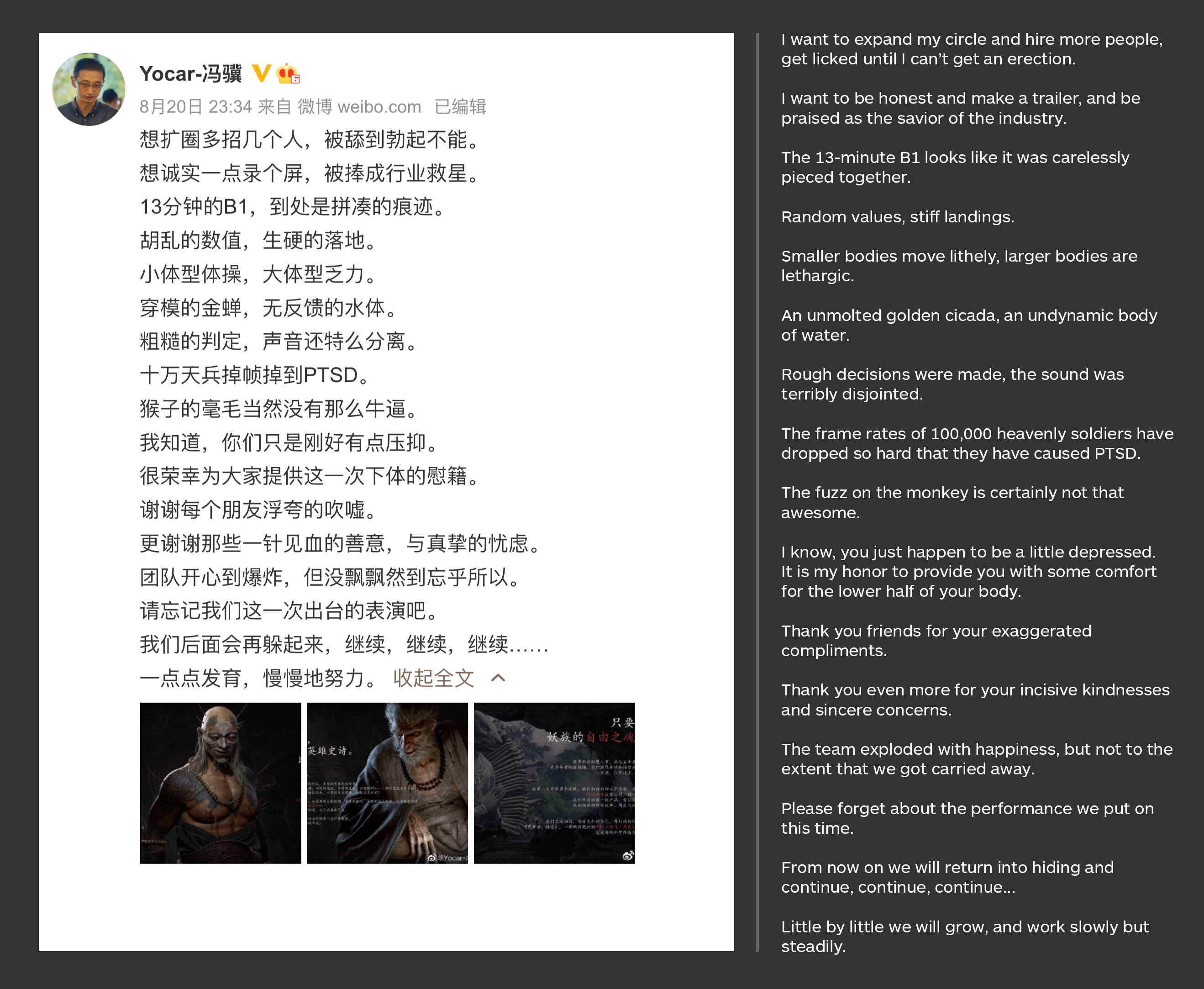

Then there’s the Weibo post that garnered significant backlash. Soon after the pre-alpha video for Black Myth: Wukong was released in August 2020, Feng penned his thoughts about the video going viral on Weibo. The post was largely about his self-criticism over the video’s lackluster production quality, with Feng Ji stating that “The 13-minute B1 looks like it was carelessly pieced together” and that the “frame rates of 100,000 heavenly soldiers have dropped so hard that they have caused PTSD.” But this was accompanied by several innuendo-laden lines. In the first line, Feng wrote, “I want to expand my circle and hire more people, get licked until I can’t get an erection.” Several lines down, he also added, “I know, you just happen to be a little depressed. It is my honor to provide you with some comfort in the lower half of your body.” He later doubled down with a separate comment, saying that “I got wet after watching it a couple of times… the pressure in my crotch is immense!”

To many who were familiar with Feng’s mannerisms, these were just the harmless quirks of a game developer who, as vulgar as he may seem, is steadfast about his vision for game-making. Several fans have excused his behavior, with them chalking this up to a straight-talking passion for game-making. “There’s no need to debate, many literary giants also use foul language, let’s just experience the work ourselves. A single beauty can cover up all the ugliness, so let’s just wait for the results. But I will support it because of their courage, and that they were able to put so much culture and history into the game,” reads one response, written in Chinese, to a video discussing the controversy.

But to other industry professionals and players, these comments felt unnecessarily crude and offputting. “I noticed that the company never really addressed the critiques directly. I know that they probably removed some of the stuff that they previously posted, but they never apologized or never acknowledged that,” says Cathy (pseudonym), a Chinese game developer who requested anonymity. “Personally, I feel that as an industry professional, I would probably still play the game just because it's really important [...] for the industry itself. But I probably wouldn't promote the game anyway, I wouldn't be supportive.”

These crude expressions, and the culture of sexism, also seem to extend to the rest of Game Science as well, even prior to the studio’s founding. In a 2014 annual meeting held at Tencent, members of the Asura Online team—some of them being the co-founders of Game Science—produced a video that poked fun at the imagined plight of its team after the game was shut down. In this video, a few male employees were depicted as adult film actors and a rapist after they lost their jobs, whereas some of its female staff had to work as nightclub hostesses and foot bath attendants (Tencent declined to comment for this piece).

And a year later in 2015, Game Science also published several recruitment posters that featured suggestive images, which IGN has seen and verified. In one poster, a risque illustration that resembles the artwork of Austrian artist Egon Schiele is accompanied by a header that says “Mandatory self-pleasure”. In another poster that featured the rear view of a woman, the ad reads, “Don’t screw your colleagues”. In the same ad, friends with benefits were also implied as an office perk. And a third poster, featuring a dumbbell, is far more pointed, with the ad stating that “fatties should fuck off”.

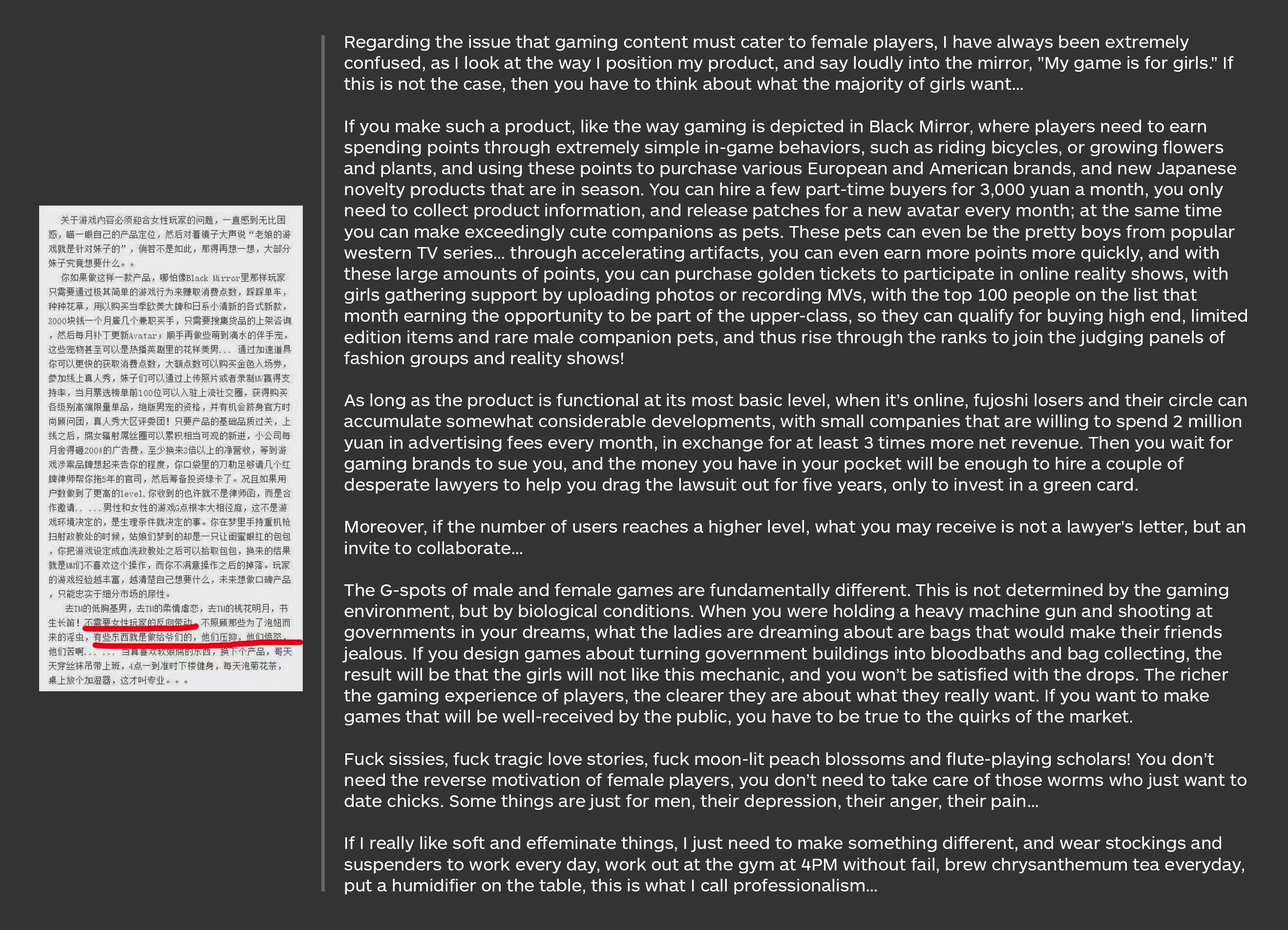

Then there is a separate Weibo post by lead artist and co-founder, Yang Qi, back in 2013, which was also unearthed by internet sleuths. In the post, Yang embarked on an extensive diatribe about how games made for women and men are completely different, due to their biological differences. In the post, he pointed out that when men “were holding a heavy machine gun and shooting at governments in your dreams, what the ladies are dreaming about are bags that would make their friends jealous.” He then concluded the post by suggesting that he would need to put on silk stockings and suspenders to work, brew chrysanthemum tea, and put a humidifier on his table to make “soft and effeminate things”.

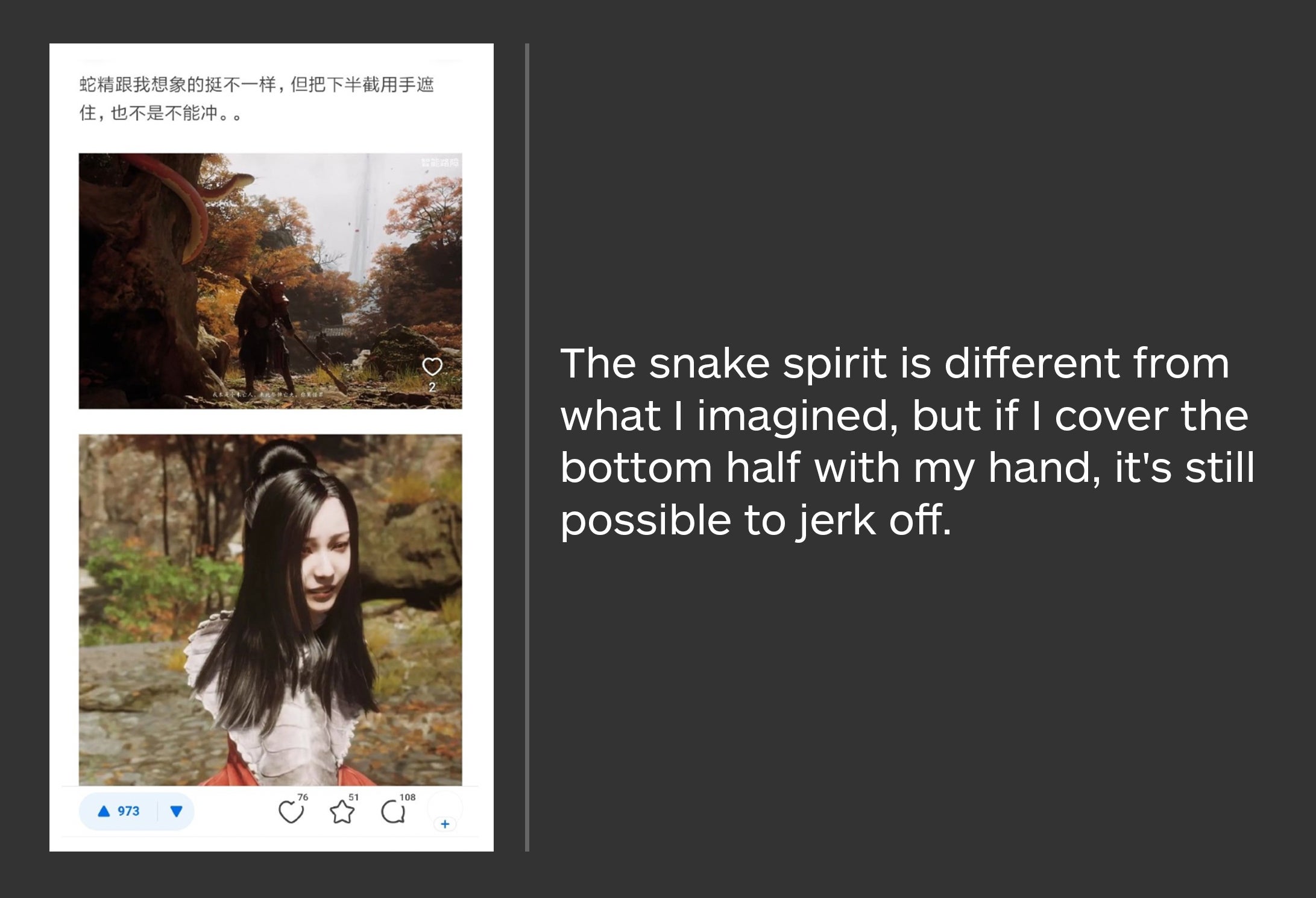

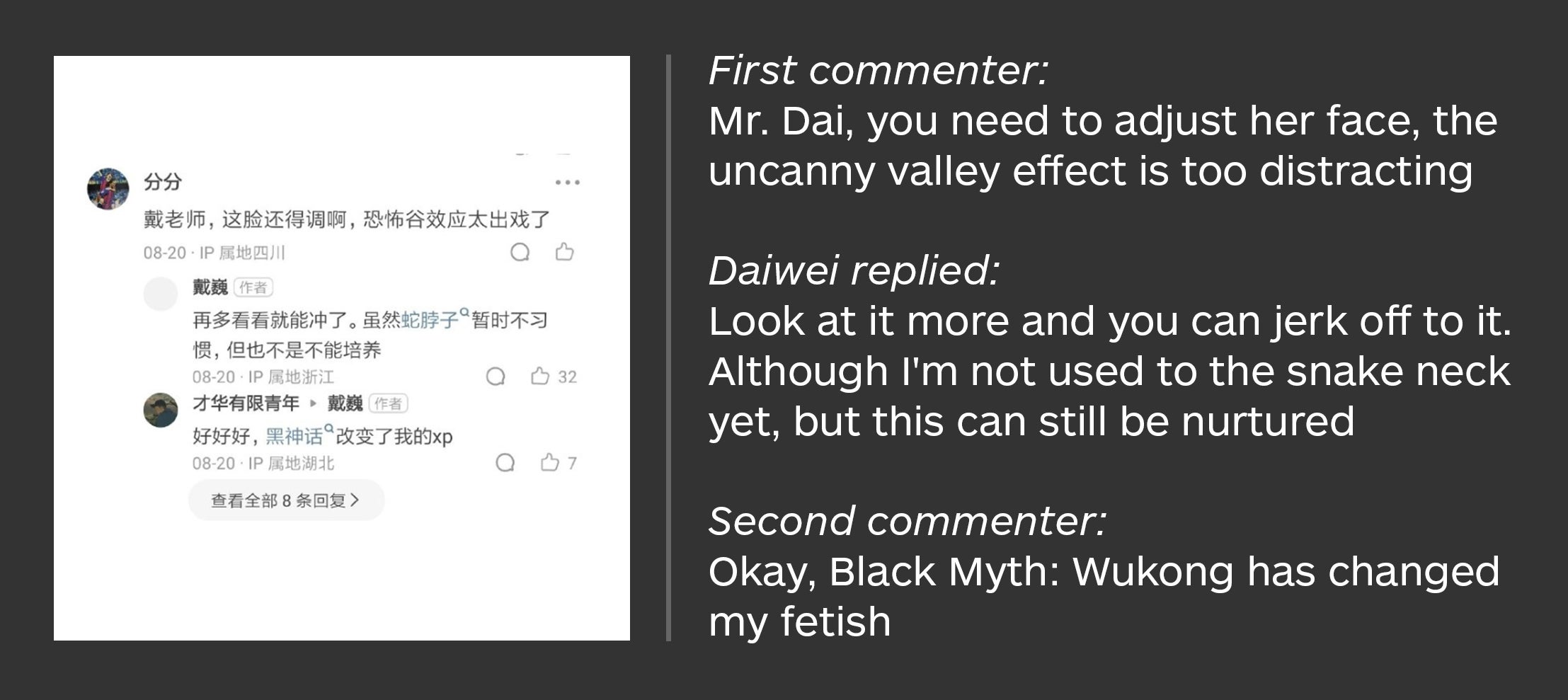

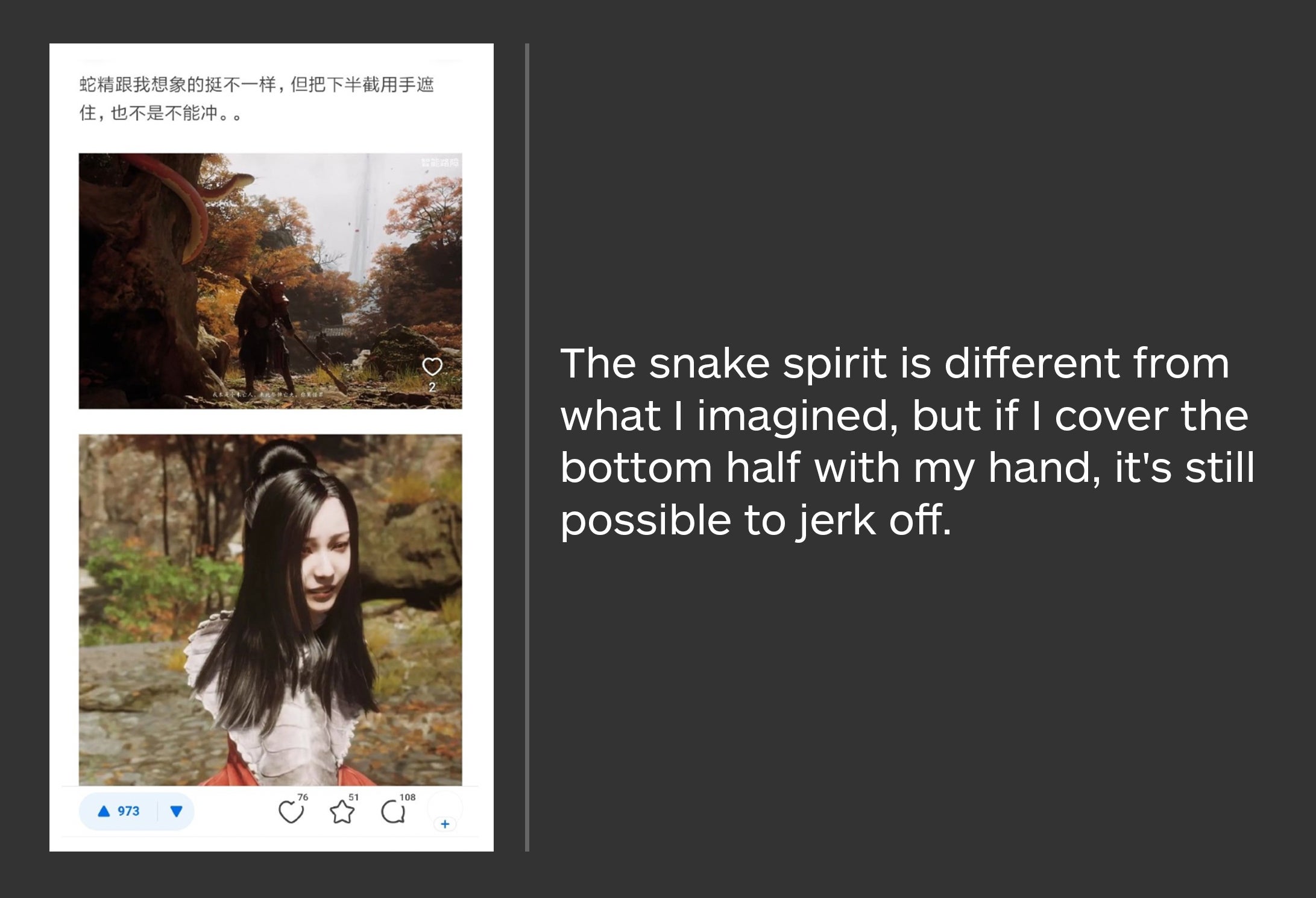

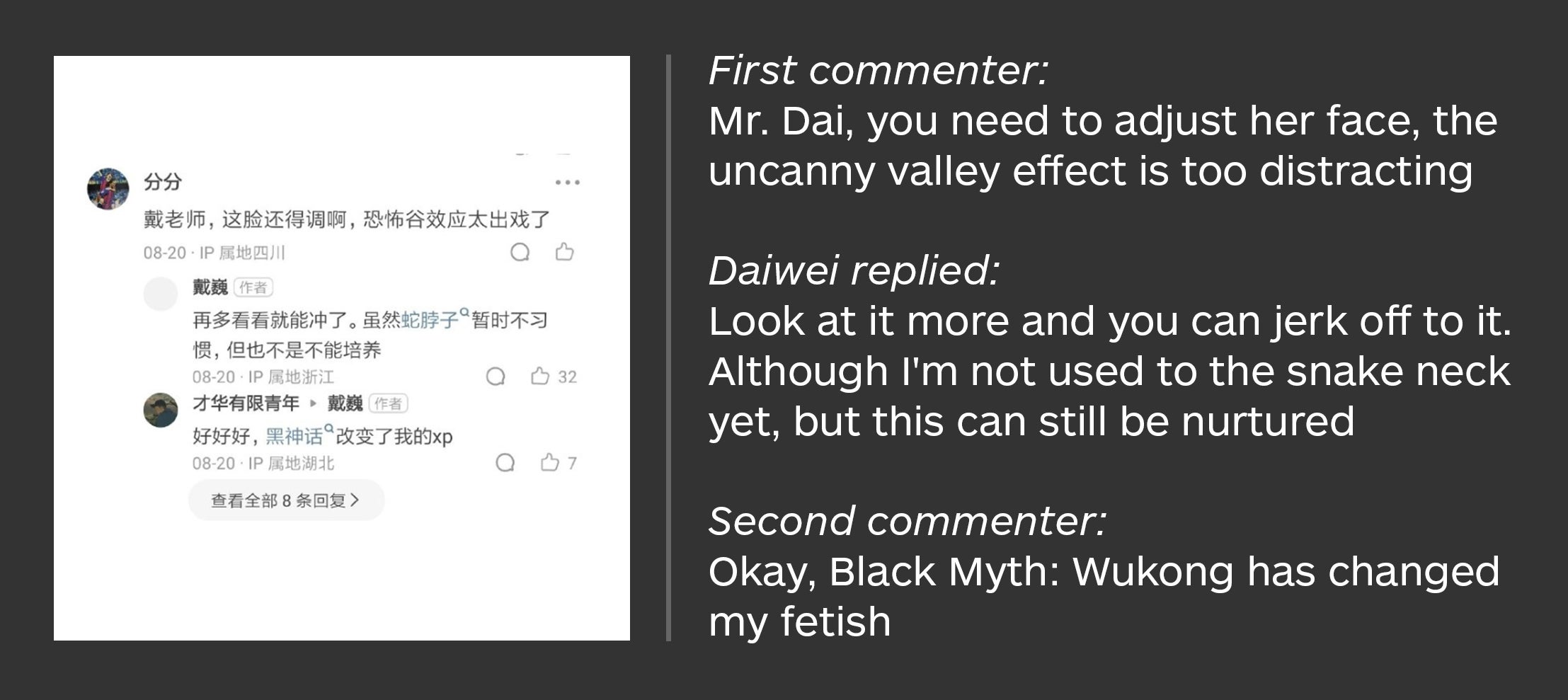

Most recently, a technical artist from Game Science, Daiwei, suggested in a post on Zhihu (the Chinese equivalent of social question-and-answer website Quora) that a female character from Black Myth: Wukong—known as the snake spirit—can be masturbated to by “looking at her more”. “Although I’m not used to the snake neck, I can still nurture that fetish,” he adds. The comment, which was posted in the wake of the release of Black Myth: Wukong’s Gamescom trailer in August 2023, has since been deleted.

Finally, there’s the Game Science logo: several Chinese netizens have pointed out that it resembles a sperm. Game Science has yet to confirm or deny this finding.

The controversies around Game Science and their potential impact on the imminent release of Black Myth: Wukong do not exist in a vacuum. In fact, one common defense of Game Science’s remarks brought forward by its supporters is that this kind of talk is commonplace and entirely unremarkable on the walled-off Chinese internet, including in gaming circles. And they’re not wrong. While China as a whole is currently seeing a growing feminist revolution, women are fighting an ongoing, uphill battle against what multiple Chinese game developers have told IGN is an historic, prevailing culture of women being thought of, spoken of, and treated as sexual objects inferior to men.

Speaking to IGN, Chinese game developer Monica F. names numerous reasons for China’s feminist struggles, including the lingering impacts of China’s one-child policy resulting in an overall gender imbalance in China and a growing population of frustrated adult men. Another issue, she says, is a broader government hostility toward feminist ideals, making it difficult for discussions to gain traction on the walled-off, heavily censored Chinese internet. Current Chinese president Xi Jinping has been particularly strict. He oversaw the detention of the Feminist Five, alongside a wave of crackdowns against women’s rights organizations and feminist online speech, including the censorship of the #MeToo and #MeTooInChina hashtag during the heyday of the online movement. And while this piece explicitly focuses on women, it’s critical to note that China’s community of nonbinary and genderqueer individuals face even greater social ostracization and discrimination.

“Feminist organization in China has been very uphill in many senses of the word,” said Rui Zhong, a board member of Chinese feminist editorial collective NüVoices, and a China research specialist. “There's been crackdowns after labor organizing efforts, there's been crackdowns over discussing marital problems, there's been definitely crackdowns after people have accused prominent Chinese men of harassment, assault or sexual misconduct, and the deck has been generally very stacked against them.”

Feminist organization in China has been very uphill in many senses of the word.

In gaming communities, these struggles are echoed and exacerbated. While a 2020 Niko Partners report identifies nearly half of the country’s gamers as women, Monica F. explains that online gaming rhetoric especially is toxic and frequently sexist in China, making it hard for women to feel safe. Zhong, too, noted that while Chinese online spaces in particular can be extremely hostile toward women, in many ways, these spaces aren’t that different from other online communities around the world. Sexism is, and continues to be, a global problem. But the difference, as both Zhong and Monica F. pointed out, is that the Chinese government and overall cultural attitudes continue to actively discourage women and their allies from fighting back. There’s no one telling harassers “no.”

It doesn’t help that, until very recently, almost all video games launching in China’s walled-off market were marketed explicitly toward men, effectively increasing perceptions that women did not belong in the space. Elva Tan, a professional in the Chinese games industry, tells us that this situation has improved in recent years, kicked off in no small part by a surge of Chinese otome games - story-based, romance-driven games initially popularized in Japan - that started with Mr Love: Queen’s Choice in 2017.

“Before the emergence of female-oriented games, all female players could only play games that were mainly focused on men,” Tan says. “After the emergence of female-oriented games, not only girls who play games discovered that there are games specially made for women, but more girls also discovered that games can also be fun. This expands the gaming population and brings further prosperity to the gaming market.”

But even with the recent recognition of women as a viable gaming market in China, their inclusion in the industry itself is an uphill battle. At best, Zhong suggests, women in tech and gaming in China are often invisible. She pointed out that while there are a small handful of prominent Chinese women in tech, such as Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, almost all major figures are men: Tencent’s “Pony” Ma Huateng, Baidu CEO Robin Li, Lenovo CEO Yang Yuanqing, NetEase CEO Ding Lei, Alibaba founder Jack Ma Yun, and many more.

And with financial and decision-making power primarily held by men, many of these tech companies have permitted work environments toxic to women to thrive. The games industry, we’re told, has similar issues. One anonymous developer showed IGN screenshots of a games industry group chat they were in, which included numerous casually sexist remarks and inappropriate nicknames. They told us they were in multiple such chats, billed as networking or chat groups for industry talk, but which often devolved into discussions that they called “very unsettling.”

One example of this manifesting that we were pointed to was from the company Duoyi Games, developer of Gunfire Reborn. At one point, its CEO Xu Bo laid off 11 female employees as part of an internal investigation, with one anonymous employee alleging that Xu Bo shared in a board meeting that he did so because he “didn’t want another feminist bitch” in the company. However, despite this report, Duoyi Games’ has suffered little to no blowback. Gunfire Reborn, its most recent release, sold two million copies on PC alone, and subsequently released ports to Xbox and PlayStation consoles, with a Nintendo Switch version on the way. Duoyi Games did not return IGN’s request for comment.

And multiple developers we spoke to were familiar with the story around a game called Retirement Simulator. The game was criticized at its early access launch last year by a number of women for a certain character’s appearance coming across as oversexualized. Developer DoubleThink Studio made adjustments to the character as well as other changes in response, only to be hit with a massive backlash from another segment of its audience for supposedly pandering to a feminist audience. Even today, the game’s Steam reviews are “Mostly Negative,” with many negative reviews seeming to refer to the change.

“Careless removal of content, change of artwork, all so that the simp developer of the game can suck up and please some extreme feminists,” read one review from last May. “Would not recommend for anyone with more than a single brain cell.”

With all this in mind, we return to Black Myth: Wukong. The various remarks about women made by its founders have spanned the last decade, during which China’s online gaming communities have undergone a major upheaval in terms of how women speak, act, and exist within them. They are contemporary with dozens of other examples of similar behavior from much larger and more successful companies, but they also exist on a global stage where women are increasingly demanding equal rights, protections, and consideration. In the midst of these incidents, with Black Myth: Wukong nearly finished and international reputation only growing, women in China are demanding the studio’s developers take the other half of the entire gaming audience into consideration at long last. But the backlash has been fierce.

Cathy recalled the reaction on Chinese social media around a recent Black Myth: Wukong Gamescom trailer, saying that many gamers in China were aware of the controversy, but women in particular were frustrated that the developers’ comments weren’t getting more media attention. Numerous posts about Game Science and Black Myth: Wukong were flooded with debate, with women and supporters pointing out and condemning Game Science’s past remarks, and others arguing back to defend the studio.

“[The] majority [of] the gaming media coverage was obviously focusing on how awesome the new trailer looks, and the demo, etc,” they said. “So the women, at least the leading voices came from women, basically started another campaign saying, ‘Hey, you basically made it clear that you don't want us to play your game, so I guess we won't play your game.’ And that got a lot of retweets on social media...Even though there are many women or many feminist supporters retweeting the post, a lot of people would go to the conversation to say very nasty things and basically that's always what happens when someone speaks out.”

As a female player I actually wanted to buy the game originally. Forget it, I’ll just keep playing foreign AAA games (bye bye).

Cathy’s summary echoes what we saw in examining the responses to the various Game Science posts, as well as online discussions on the subject. Opinions span a wide gamut from outrage to defensiveness, with numerous women and their allies expressing hurt and anger at what was said. Some declared an intent not to play the game, or expressed uncertainty due to a conflicting desire to support Chinese development. “Okay okay, he definitely doesn’t need money from a female player like myself,” said one Weibo commenter. “So gross, as a female player I actually wanted to buy the game originally. Forget it, I’ll just keep playing foreign AAA games (bye bye),” wrote another.

In response, detractors diminished the severity of Game Science’s remarks while defending Black Myth’s status as a potential massive breakout game for the Chinese industry -- one that would cement the country’s place in the global games conversation after years of insular development. That success, many argued, did not need to involve women. “AAA games and most games actually don’t need female players,” one person commented on Douban. “What about the pitiful sales you contribute? Can it save Game Science from fire or something?”

Another wrote, “There are actually no female players! Let’s throw flowers, this is great! Game of the year at TGA [The Game Awards] is secured.”

Conversations viewed by IGN included numerous sexual, harassing, derogatory, and even threatening remarks made toward women critical of Game Science. Multiple women who were particularly outspoken on the subject appear to have deleted or locked their social media accounts, seemingly due to a deluge of harassment for speaking against the game.

“I hope gamers overseas are made aware of all this — not to encourage them to boycott the game, but I think consumers should know about the stance of the creators before making a purchase,” Jen told us. “These male developers have never paid the price for their misogynistic remarks. Furthermore, when female gamers express their dissatisfaction, we can easily be attacked. It's time for this to change.”

Black Myth: Wukong’s controversy sits at an inflection point not just for Chinese feminism, but also for the Chinese games industry. While a handful of breakout hits such as Genshin Impact have gained global attention in recent years, China has still struggled to produce many games with international appeal. Black Myth: Wukong’s reception at Gamescom Opening Night Live and other events indicates it may be the difference maker (ONL creator Geoff Keighley did not return our request for comment). But while that’s good news for the industry, it’s having the knock-on effect of putting Game Science on a global stage - one that may treat its past remarks with less generosity.

“They intend to release this game internationally, the company should not expect to just coast on nice looking gameplay,” Zhong said. “Granted, the one thing they have going is Western games are sexist as well…I think they would probably just expect to coast on the status quo, and people ignoring misogyny, but that's the risk that that company chooses to take.”

In light of all this, Game Science may have found itself backed into a corner. If its remarks circulate more widely to a Western audience, it risks Black Myth: Wukong being condemned. But in China, its audience is full of fervent defenders of its past actions. Should the studio apologize, and risk alienating the supporters it gained from the stance it’s perceived to have taken over the years? Will it?

This backdrop of sexism within Game Science and the industry seems to be in stark contrast to the very themes of Journey to the West at times, a tale about overcoming trials and tribulations in a legendary pilgrimage. One of its central characters, Zhu Bajie (or Pigsy), was the commander-in-chief of a celestial army, and was banished to Earth after harassing the moon goddess Chang’e. Known for his gluttony and lust, he didn’t achieve enlightenment to become an arhat, unlike his fellow pilgrims. Then there’s Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion and the goddess of mercy. Notably, we have not yet seen Guanyin make an appearance in Black Myth: Wukong’s trailers. But Guanyin plays a central role in Journey to the West who helps the pilgrims on their journey—an irony that’s also not lost on Zhong.

“I just remember Sun Wukong going, "We have a lot of problems right now, and I need your help." And Guanyin's like, "Okay, fine,” and [that] solves the problem,” she adds. “Which is because she's the bodhisattva of compassion, so she'll do it out of the goodness of her heart, which is also kind of sexist in its own way of, "You're a woman, you've got to clean up the dudes' messes."

It remains to be seen if Game Science will acknowledge these allegations, or even acknowledge the role of women in Black Myth: Wukong both as characters and audience members. But for many female players and developers, the sexism of the games community in China continues to be difficult to grapple with, exacerbated by the actions of an increasingly prominent studio like Game Science. “Do you get it now? In mainland China, even a slight gesture of respect towards female gamers can lead to massive backlash,” says Jen. “In their eyes, women don't deserve respect. Even just listening to them is considered pandering, a marketing tactic, and catering to Western political correctness. I can't describe how despairing this feels.”

Rebekah Valentine is a senior reporter for IGN. Khee Hoon Chan is a freelance writer from the internet. They can also be found on other publications, including Polygon, Edge Magazine and PC Gamer.

Disclosure: One of the co-authors of this piece has a personal relationship with a former employee (2021-2022) of a Tencent subsidiary.

Continue reading...

The global buzz around Black Myth: Wukong may be gradually reaching fever pitch, but the excitement over the game feels like it has peaked back in China, with local publications referring to Black Myth: Wukong as the pinnacle of locally-made AAA games. When it was introduced in 2020 with a 13-minute pre-alpha trailer, Black Myth: Wukong was met with international acclaim for its sleek, cinematic visuals and high-octane, high-fantasy combat scenes. Within a day of its release, the video had garnered 2 million views on Youtube and 10 million views on Chinese streaming site Bilibili. At the height of this commotion around Black Myth: Wukong, Game Science even had to fend off unsolicited visitors at its studio by putting up a notice outside its premises, according to a report from IGN China. One intruder, who thought the office would be vacant on a Saturday afternoon, broke into the building through a window to pay the studio a visit—a stunt that shocked the employees who were working at the office over the weekend. In another incident, a visitor abruptly turned up at the door, declaring that they had quit their job to participate in the game’s development.

For an indie studio that has only released mobile titles within the country, this widespread acclaim over Black Myth: Wukong is a largely unprecedented feat, particularly for a game that has not been released yet. But beneath the luster of this souls-like is a studio plagued by claims of sexism. Several posts have surfaced from Chinese social media site Weibo, written by individuals from the studio, that contain multiple references to genitalia and sexual innuendos. These have provoked a backlash among some in the games community, many of whom are women. This was coupled by recruitment posters by the studio, produced in 2015, which featured images and headlines that point to a culture of ingrained sexism in Game Science.

IGN spoke to several women familiar with gaming culture, as well as the games and technology industry, in China, many of whom requested to be anonymous for fear of backlash from fans of Game Science and the broader games community. “In the eyes of many female players, [Game Science] has a notably negative reputation,” said Jen (pseudonym), a Chinese games designer who’s now based outside of China. “I admire their dedication and work. I had high expectations for their game, until I came across their misogynistic remarks around 2021, which was reported in the news.”

IGN reached out to Game Science ahead of the publication of this article, but the studio did not respond to a request for comment on any of the allegations.

[CW: This article contains a number of quotes from Game Science that contain graphic sexual content and remarks.]

Founded in 2014, Game Science is a Hangzhou-based studio formed initially by seven ex-Tencent Games employees. During their time in Tencent Games, they worked on a free-to-play MMORPG called Asura Online. Black Myth: Wukong can be said to be the spiritual successor of this MMO, with both games based on the Chinese literary classic “Journey to the West”. Asura Online also featured mythological figures from the novel, such as Sun Wukong, the Bull Demon King, and Erlang Shen alongside a dark retelling of the novel, filled with several cinematic sequences. But to many of its fans, these were derailed by Tencent’s push for microtransactions in the game—a change that, according to one player, swiftly knocked Asura Online off the altar and turned it into a “trash game”. A year later, Feng Ji, one of the co-founders of Game Science, left to form Game Science along with his colleagues. After releasing a slew of mobile games, Game Science decided to focus on the development of Black Myth: Wukong in 2017.

Feng, in particular, has an outsized presence within the games industry, with a penchant for sharing introspective insights on game development, peppered with crude metaphors and boorish innuendos. In 2007, he penned a lengthy article titled, “Who has murdered our game?”, where he delved into the difficulties of game development in China. Feng compared failed projects to stillborn babies, given that many games had to cease development despite being worked on for a year or so. He then brought up this analogy:

“Is it because the sperm isn’t virile enough? Is the pregnancy too short? Is the baby lacking nutrition? Are the doctors in charge of caesarean sections lowly skilled? Why can’t we produce a healthy child (product)?”

Then there’s the Weibo post that garnered significant backlash. Soon after the pre-alpha video for Black Myth: Wukong was released in August 2020, Feng penned his thoughts about the video going viral on Weibo. The post was largely about his self-criticism over the video’s lackluster production quality, with Feng Ji stating that “The 13-minute B1 looks like it was carelessly pieced together” and that the “frame rates of 100,000 heavenly soldiers have dropped so hard that they have caused PTSD.” But this was accompanied by several innuendo-laden lines. In the first line, Feng wrote, “I want to expand my circle and hire more people, get licked until I can’t get an erection.” Several lines down, he also added, “I know, you just happen to be a little depressed. It is my honor to provide you with some comfort in the lower half of your body.” He later doubled down with a separate comment, saying that “I got wet after watching it a couple of times… the pressure in my crotch is immense!”

To many who were familiar with Feng’s mannerisms, these were just the harmless quirks of a game developer who, as vulgar as he may seem, is steadfast about his vision for game-making. Several fans have excused his behavior, with them chalking this up to a straight-talking passion for game-making. “There’s no need to debate, many literary giants also use foul language, let’s just experience the work ourselves. A single beauty can cover up all the ugliness, so let’s just wait for the results. But I will support it because of their courage, and that they were able to put so much culture and history into the game,” reads one response, written in Chinese, to a video discussing the controversy.

But to other industry professionals and players, these comments felt unnecessarily crude and offputting. “I noticed that the company never really addressed the critiques directly. I know that they probably removed some of the stuff that they previously posted, but they never apologized or never acknowledged that,” says Cathy (pseudonym), a Chinese game developer who requested anonymity. “Personally, I feel that as an industry professional, I would probably still play the game just because it's really important [...] for the industry itself. But I probably wouldn't promote the game anyway, I wouldn't be supportive.”

These crude expressions, and the culture of sexism, also seem to extend to the rest of Game Science as well, even prior to the studio’s founding. In a 2014 annual meeting held at Tencent, members of the Asura Online team—some of them being the co-founders of Game Science—produced a video that poked fun at the imagined plight of its team after the game was shut down. In this video, a few male employees were depicted as adult film actors and a rapist after they lost their jobs, whereas some of its female staff had to work as nightclub hostesses and foot bath attendants (Tencent declined to comment for this piece).

And a year later in 2015, Game Science also published several recruitment posters that featured suggestive images, which IGN has seen and verified. In one poster, a risque illustration that resembles the artwork of Austrian artist Egon Schiele is accompanied by a header that says “Mandatory self-pleasure”. In another poster that featured the rear view of a woman, the ad reads, “Don’t screw your colleagues”. In the same ad, friends with benefits were also implied as an office perk. And a third poster, featuring a dumbbell, is far more pointed, with the ad stating that “fatties should fuck off”.

Then there is a separate Weibo post by lead artist and co-founder, Yang Qi, back in 2013, which was also unearthed by internet sleuths. In the post, Yang embarked on an extensive diatribe about how games made for women and men are completely different, due to their biological differences. In the post, he pointed out that when men “were holding a heavy machine gun and shooting at governments in your dreams, what the ladies are dreaming about are bags that would make their friends jealous.” He then concluded the post by suggesting that he would need to put on silk stockings and suspenders to work, brew chrysanthemum tea, and put a humidifier on his table to make “soft and effeminate things”.

Most recently, a technical artist from Game Science, Daiwei, suggested in a post on Zhihu (the Chinese equivalent of social question-and-answer website Quora) that a female character from Black Myth: Wukong—known as the snake spirit—can be masturbated to by “looking at her more”. “Although I’m not used to the snake neck, I can still nurture that fetish,” he adds. The comment, which was posted in the wake of the release of Black Myth: Wukong’s Gamescom trailer in August 2023, has since been deleted.

Finally, there’s the Game Science logo: several Chinese netizens have pointed out that it resembles a sperm. Game Science has yet to confirm or deny this finding.

The controversies around Game Science and their potential impact on the imminent release of Black Myth: Wukong do not exist in a vacuum. In fact, one common defense of Game Science’s remarks brought forward by its supporters is that this kind of talk is commonplace and entirely unremarkable on the walled-off Chinese internet, including in gaming circles. And they’re not wrong. While China as a whole is currently seeing a growing feminist revolution, women are fighting an ongoing, uphill battle against what multiple Chinese game developers have told IGN is an historic, prevailing culture of women being thought of, spoken of, and treated as sexual objects inferior to men.

Speaking to IGN, Chinese game developer Monica F. names numerous reasons for China’s feminist struggles, including the lingering impacts of China’s one-child policy resulting in an overall gender imbalance in China and a growing population of frustrated adult men. Another issue, she says, is a broader government hostility toward feminist ideals, making it difficult for discussions to gain traction on the walled-off, heavily censored Chinese internet. Current Chinese president Xi Jinping has been particularly strict. He oversaw the detention of the Feminist Five, alongside a wave of crackdowns against women’s rights organizations and feminist online speech, including the censorship of the #MeToo and #MeTooInChina hashtag during the heyday of the online movement. And while this piece explicitly focuses on women, it’s critical to note that China’s community of nonbinary and genderqueer individuals face even greater social ostracization and discrimination.

“Feminist organization in China has been very uphill in many senses of the word,” said Rui Zhong, a board member of Chinese feminist editorial collective NüVoices, and a China research specialist. “There's been crackdowns after labor organizing efforts, there's been crackdowns over discussing marital problems, there's been definitely crackdowns after people have accused prominent Chinese men of harassment, assault or sexual misconduct, and the deck has been generally very stacked against them.”

Feminist organization in China has been very uphill in many senses of the word.

In gaming communities, these struggles are echoed and exacerbated. While a 2020 Niko Partners report identifies nearly half of the country’s gamers as women, Monica F. explains that online gaming rhetoric especially is toxic and frequently sexist in China, making it hard for women to feel safe. Zhong, too, noted that while Chinese online spaces in particular can be extremely hostile toward women, in many ways, these spaces aren’t that different from other online communities around the world. Sexism is, and continues to be, a global problem. But the difference, as both Zhong and Monica F. pointed out, is that the Chinese government and overall cultural attitudes continue to actively discourage women and their allies from fighting back. There’s no one telling harassers “no.”

It doesn’t help that, until very recently, almost all video games launching in China’s walled-off market were marketed explicitly toward men, effectively increasing perceptions that women did not belong in the space. Elva Tan, a professional in the Chinese games industry, tells us that this situation has improved in recent years, kicked off in no small part by a surge of Chinese otome games - story-based, romance-driven games initially popularized in Japan - that started with Mr Love: Queen’s Choice in 2017.

“Before the emergence of female-oriented games, all female players could only play games that were mainly focused on men,” Tan says. “After the emergence of female-oriented games, not only girls who play games discovered that there are games specially made for women, but more girls also discovered that games can also be fun. This expands the gaming population and brings further prosperity to the gaming market.”

But even with the recent recognition of women as a viable gaming market in China, their inclusion in the industry itself is an uphill battle. At best, Zhong suggests, women in tech and gaming in China are often invisible. She pointed out that while there are a small handful of prominent Chinese women in tech, such as Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, almost all major figures are men: Tencent’s “Pony” Ma Huateng, Baidu CEO Robin Li, Lenovo CEO Yang Yuanqing, NetEase CEO Ding Lei, Alibaba founder Jack Ma Yun, and many more.

And with financial and decision-making power primarily held by men, many of these tech companies have permitted work environments toxic to women to thrive. The games industry, we’re told, has similar issues. One anonymous developer showed IGN screenshots of a games industry group chat they were in, which included numerous casually sexist remarks and inappropriate nicknames. They told us they were in multiple such chats, billed as networking or chat groups for industry talk, but which often devolved into discussions that they called “very unsettling.”

One example of this manifesting that we were pointed to was from the company Duoyi Games, developer of Gunfire Reborn. At one point, its CEO Xu Bo laid off 11 female employees as part of an internal investigation, with one anonymous employee alleging that Xu Bo shared in a board meeting that he did so because he “didn’t want another feminist bitch” in the company. However, despite this report, Duoyi Games’ has suffered little to no blowback. Gunfire Reborn, its most recent release, sold two million copies on PC alone, and subsequently released ports to Xbox and PlayStation consoles, with a Nintendo Switch version on the way. Duoyi Games did not return IGN’s request for comment.

And multiple developers we spoke to were familiar with the story around a game called Retirement Simulator. The game was criticized at its early access launch last year by a number of women for a certain character’s appearance coming across as oversexualized. Developer DoubleThink Studio made adjustments to the character as well as other changes in response, only to be hit with a massive backlash from another segment of its audience for supposedly pandering to a feminist audience. Even today, the game’s Steam reviews are “Mostly Negative,” with many negative reviews seeming to refer to the change.

“Careless removal of content, change of artwork, all so that the simp developer of the game can suck up and please some extreme feminists,” read one review from last May. “Would not recommend for anyone with more than a single brain cell.”

With all this in mind, we return to Black Myth: Wukong. The various remarks about women made by its founders have spanned the last decade, during which China’s online gaming communities have undergone a major upheaval in terms of how women speak, act, and exist within them. They are contemporary with dozens of other examples of similar behavior from much larger and more successful companies, but they also exist on a global stage where women are increasingly demanding equal rights, protections, and consideration. In the midst of these incidents, with Black Myth: Wukong nearly finished and international reputation only growing, women in China are demanding the studio’s developers take the other half of the entire gaming audience into consideration at long last. But the backlash has been fierce.

Cathy recalled the reaction on Chinese social media around a recent Black Myth: Wukong Gamescom trailer, saying that many gamers in China were aware of the controversy, but women in particular were frustrated that the developers’ comments weren’t getting more media attention. Numerous posts about Game Science and Black Myth: Wukong were flooded with debate, with women and supporters pointing out and condemning Game Science’s past remarks, and others arguing back to defend the studio.

“[The] majority [of] the gaming media coverage was obviously focusing on how awesome the new trailer looks, and the demo, etc,” they said. “So the women, at least the leading voices came from women, basically started another campaign saying, ‘Hey, you basically made it clear that you don't want us to play your game, so I guess we won't play your game.’ And that got a lot of retweets on social media...Even though there are many women or many feminist supporters retweeting the post, a lot of people would go to the conversation to say very nasty things and basically that's always what happens when someone speaks out.”

As a female player I actually wanted to buy the game originally. Forget it, I’ll just keep playing foreign AAA games (bye bye).

Cathy’s summary echoes what we saw in examining the responses to the various Game Science posts, as well as online discussions on the subject. Opinions span a wide gamut from outrage to defensiveness, with numerous women and their allies expressing hurt and anger at what was said. Some declared an intent not to play the game, or expressed uncertainty due to a conflicting desire to support Chinese development. “Okay okay, he definitely doesn’t need money from a female player like myself,” said one Weibo commenter. “So gross, as a female player I actually wanted to buy the game originally. Forget it, I’ll just keep playing foreign AAA games (bye bye),” wrote another.

In response, detractors diminished the severity of Game Science’s remarks while defending Black Myth’s status as a potential massive breakout game for the Chinese industry -- one that would cement the country’s place in the global games conversation after years of insular development. That success, many argued, did not need to involve women. “AAA games and most games actually don’t need female players,” one person commented on Douban. “What about the pitiful sales you contribute? Can it save Game Science from fire or something?”

Another wrote, “There are actually no female players! Let’s throw flowers, this is great! Game of the year at TGA [The Game Awards] is secured.”

Conversations viewed by IGN included numerous sexual, harassing, derogatory, and even threatening remarks made toward women critical of Game Science. Multiple women who were particularly outspoken on the subject appear to have deleted or locked their social media accounts, seemingly due to a deluge of harassment for speaking against the game.

“I hope gamers overseas are made aware of all this — not to encourage them to boycott the game, but I think consumers should know about the stance of the creators before making a purchase,” Jen told us. “These male developers have never paid the price for their misogynistic remarks. Furthermore, when female gamers express their dissatisfaction, we can easily be attacked. It's time for this to change.”

Black Myth: Wukong’s controversy sits at an inflection point not just for Chinese feminism, but also for the Chinese games industry. While a handful of breakout hits such as Genshin Impact have gained global attention in recent years, China has still struggled to produce many games with international appeal. Black Myth: Wukong’s reception at Gamescom Opening Night Live and other events indicates it may be the difference maker (ONL creator Geoff Keighley did not return our request for comment). But while that’s good news for the industry, it’s having the knock-on effect of putting Game Science on a global stage - one that may treat its past remarks with less generosity.

“They intend to release this game internationally, the company should not expect to just coast on nice looking gameplay,” Zhong said. “Granted, the one thing they have going is Western games are sexist as well…I think they would probably just expect to coast on the status quo, and people ignoring misogyny, but that's the risk that that company chooses to take.”

In light of all this, Game Science may have found itself backed into a corner. If its remarks circulate more widely to a Western audience, it risks Black Myth: Wukong being condemned. But in China, its audience is full of fervent defenders of its past actions. Should the studio apologize, and risk alienating the supporters it gained from the stance it’s perceived to have taken over the years? Will it?

This backdrop of sexism within Game Science and the industry seems to be in stark contrast to the very themes of Journey to the West at times, a tale about overcoming trials and tribulations in a legendary pilgrimage. One of its central characters, Zhu Bajie (or Pigsy), was the commander-in-chief of a celestial army, and was banished to Earth after harassing the moon goddess Chang’e. Known for his gluttony and lust, he didn’t achieve enlightenment to become an arhat, unlike his fellow pilgrims. Then there’s Guanyin, the bodhisattva of compassion and the goddess of mercy. Notably, we have not yet seen Guanyin make an appearance in Black Myth: Wukong’s trailers. But Guanyin plays a central role in Journey to the West who helps the pilgrims on their journey—an irony that’s also not lost on Zhong.

“I just remember Sun Wukong going, "We have a lot of problems right now, and I need your help." And Guanyin's like, "Okay, fine,” and [that] solves the problem,” she adds. “Which is because she's the bodhisattva of compassion, so she'll do it out of the goodness of her heart, which is also kind of sexist in its own way of, "You're a woman, you've got to clean up the dudes' messes."

It remains to be seen if Game Science will acknowledge these allegations, or even acknowledge the role of women in Black Myth: Wukong both as characters and audience members. But for many female players and developers, the sexism of the games community in China continues to be difficult to grapple with, exacerbated by the actions of an increasingly prominent studio like Game Science. “Do you get it now? In mainland China, even a slight gesture of respect towards female gamers can lead to massive backlash,” says Jen. “In their eyes, women don't deserve respect. Even just listening to them is considered pandering, a marketing tactic, and catering to Western political correctness. I can't describe how despairing this feels.”

Rebekah Valentine is a senior reporter for IGN. Khee Hoon Chan is a freelance writer from the internet. They can also be found on other publications, including Polygon, Edge Magazine and PC Gamer.

Disclosure: One of the co-authors of this piece has a personal relationship with a former employee (2021-2022) of a Tencent subsidiary.

Continue reading...